©1995 Mary Kent. All Rights Reserved.

We invite Salsa Music Lovers to visit our website and link to these pages. All Photos © 1991-1997 Mary Kent. All rights reserved. Unauthorized duplication, distribution or usage is prohibited by law.

He was born July 3,1950 in the same hospital as Tito Puente; raised by his Puerto Rican parents in Spanish Harlem, a.k.a. El Barrio, New York City. Torres's mother, a hospital worker; his father an inventive plumber, sparked Eddie's knack for inventing. No dancers or musicians in the gene pool to Eddie's best knowledge.

He was merely 12 years old when he caught the dancing bug. Just back in New York after a two year sojourn in Puerto Rico, he developed a puppy-love crush on a girl from the hood. Shyly, he asked her to the movies and she made a counter-offer: why didn't he come to her house? That Saturday, when Renée opened the door, Eddie was surprised to see a tall, good-looking guy sitting on the couch. Renée whispered apologetically, "He's my ex-boyfriend. He's looking to make up with me." Then, in an attempt to break the tension, she asked Eddie, "Do you know how to Latin?" She wanted to know if he knew how to dance Latin. Fresh from Puerto Rico, his confidence emboldened him. Renée leaned over the record player and dropped the needle on the groove of Eddie Palmieri's Azucar Pa' Ti. Not knowing a thing about leading position or about timing, the young suitor started jumping around, then glanced over to collect looks of approval. But his rival on the couch sat clamping his jaw closed, holding back a burst of laughter. Two minutes into the number, Renée retired her inexperienced partner, pulled her ex-boyfriend up and explained in a professorial manner, "Let me show you the way WE do the Latin." It was plain to see that there was a lot of coordination, plenty of moving together and all sorts of turns. The more they danced, the worse Eddie felt. After the dance demonstration, his love interest pulled him to one side and explained, "He really wants to make up with me." From that moment, Eddie made himself a promise, "This is never going to happen to me again. I'm going to learn how to dance."

The idea of learning "to dance Latin" became an obsession. Schooling took the form of going to all the clubs and hanging out with all the good dancers--watching, imitating, asking, and being a pest. Slowly he started to learn the foundations of the dance.

In those days, not many clubs allowed teenagers in, but the famous Hunts Point Palace opened every Sunday from noon to midnight, and for $5, they presented five top Latin bands, back-to-back, on two stages. Fifteen-year-old Eddie punched the clock when the club opened and sauntered out at closing time, exhausted but determined to learn.

Eight years later, he was teaching and competing in dance contests and garnering a reputation amongst the good dancers as being one of the best. One night, while he was dancing in a head-to-toe white outfit, in a club lit with nothing but black lights, his sister pulled him off the floor. It seems Renée, his childhood flame, spotted a slick dancer and wanted an intro. In the dark, Eddie's sister did the honors."Renée, I want you to meet Eddie." Upon recognizing the skillful dancer, she froze as if she'd seen ten ghosts. Eddie wanted to dance with her desperately, he wanted to thank her, "You're the reason why I got into this." But she disappeared and that was the last time he saw her.

LEARNING THE BASICS

There were no studios where one could learn how to dance this style, so the nightclub scene was the nurturing ground for aspiring dancers. And not all dancers were generous. "There were dancers who didn't even want you to look at their steps, 'cause they didn't want you to learn: That's private stock!" Lucky for Eddie, he had a knack for picking up steps just by watching. He observed dancers like Louie Máquina, who got his nickname from his "real rapid-fire footwork"; Gerard, a dancer known for his scandalous antics on the floor; George Boscones, the teacher of the newcomers and especially Jo-Jo Smith, a professional jazz teacher with a unique style of mambo jazz dancing.

There were no studios where one could learn how to dance this style, so the nightclub scene was the nurturing ground for aspiring dancers. And not all dancers were generous. "There were dancers who didn't even want you to look at their steps, 'cause they didn't want you to learn: That's private stock!" Lucky for Eddie, he had a knack for picking up steps just by watching. He observed dancers like Louie Máquina, who got his nickname from his "real rapid-fire footwork"; Gerard, a dancer known for his scandalous antics on the floor; George Boscones, the teacher of the newcomers and especially Jo-Jo Smith, a professional jazz teacher with a unique style of mambo jazz dancing.

The pros of that time were Freddy Rios, the Cha Cha Aces, Tommy Johnson and the one team who were the greatest influence of all, the prima donna team: Augie and Margo. After the first time Eddie saw them at Roseland, he was in such a state of euphoria that he couldn't sleep for weeks. He kept thinking, "I want to be Augie and I have to find Margo."

As soon as he learned to hold his own, he set up shop as a dance teacher, because he wanted to share his knowledge. Armed with a rented phonograph and a bunch of friends, he was soon in business. With no concept of timing, technique or theory, his instruction consisted of rudimentary pointers: "You hear that accent? That means you break forward with the left foot and when you hear it again, you break back." This is known as dancing on two, Eddie would soon find out. Breaking on two meant that of a four beat measure, you stepped forward with the left foot on the second beat and on the second beat second measure you stepped back on the right foot. According to Eddie's mentor, Tito Puente, that's why beat two is so popular, because it compliments the tumbao of the conga and the rhythm section.

TITO, PLEASE

From 1975 to about 1986, the Corso nightclub on East 86th Street became home to the second generation of the Palladium era. Wednesdays, Fridays, Saturdays and Sundays found Eddie Torres strutting his Harlem steps to the likes of T.P. and Machito. From the beginning, Tito Puente's music really spoke to him. This was during the years that Puente had the ass-kicking band with Santos Colón. Testing his skill in dance contests, Torres garnered so many awards that at one point, Marty Ahret, Corso's owner, asked him to sit out the contests and judge.

One Sunday evening, as Tito Puente came off the stage, Eddie approached the maestro to pay his compliments. Tito perceived Eddie's flair, "You've got talent for dancing. You need to do something more than just spend all your time here dancing socially." "There's no mentors," Eddie retorted. Tito whipped around, "Forget about mentors. Develop your own ideas and put a little act together. Figure it out yourself." Emboldened, Eddie persisted, "If I had an act, could we do some work together?" "Get something together and show me." All Eddie ever wanted to do was to dance with Tito's band.

Eight years lapsed before Eddie met Maria, his future wife and partner. His years of dancing and observing had evolved into a unique technique and style. Maria, a children's gymnastics teacher, felt rather intimidated at first, but quickly became Eddie's best student, learning faster than anyone he'd ever taught. "I would do a step and she would reflect it right back to me." But her style was provincial and lacked the Big Apple pizazz. Prompted by the possibilities, Eddie choreographed his first two tunes, El Cayuco and Palladium Days by Tito Puente, and trained Maria. In less than a year, she became a good stage dancer, but she didn't have any experience in club dancing. So when Eddie introduced Maria at the clubs as his new partner, his friends didn't think she had it. A couple of years later, they conceded, "You know, Eddie, she's getting pretty good." By the third year, they agreed, she was the best partner he'd ever had.

Filled with enthusiasm over his partner work, Eddie decided it was time to talk to Tito. Performing at Christopher's Cafe, in El Barrio, Mr. Puente spotted Eddie, "You're the dancer from the Corso." Torres offered him a makeshift business card, and pitched, "Do you think I can come over with my partner and demonstrate for you these two numbers that I choreographed? If you like them, maybe we could do a show with you?" Tito did not mince words, "You know, I'll be honest with you, Eddie. I'm very busy right now. I don't think I'll have a chance to call you...." Eddie frowned. "...But I'll tell you what I'll do. I'm going to introduce you to my musical director, Jimmy Frisaura. Tell Jimmy exactly what you want in the music, how you want us to play it, and in our next concert, I'll feature you with your partner." Eddie was flabbergasted.

The year was 1980. It was a dream come true-the debut show with Tito Puente took place at the New York Coliseum as part of a big Latin Expo. Eddie was really nervous, but he and his partner, Maria, were very prepared. They performed Cayuco first and then broke out into Palladium Days. The crowd was captivated and Tito had a big smile on his face. It was a total success.

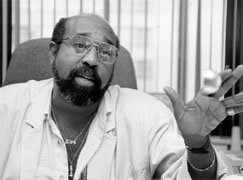

Eddie Torres & Tito Puente have a friendly discussion.

Eddie Torres & Tito Puente have a friendly discussion.

From that day forward, everywhere Tito went, Eddie would follow, costume and shoes, ready to go. And Tito would always ask, "You guys like to do a number?" It was ad honorem, but Torres felt privileged to be working with Tito. Eventually, Torres became a fixture--part of the format of the show. Then he popped the question, "Tito, would you mind if we call ourselves the Tito Puente Dancers?" That dream, to be identified as Tito's dance team, took the form of a jacket with TP's picture playing timbales--it said Tito Puente Dancers, and Tito dug it. It was Eddie's biggest honor. Even more so when Jimmy Frisaura confided, "Tito doesn't share the stage with anybody too readily. He likes you."

WE WANT LATIN

In the mid-eighties, Latin was out and the hustle was in and it was very hard to get work as a Latin dancer. On one occasion, Eddie wanted to dance in a Latin concert at Madison Square Garden where Tito Puente was playing, but Ralph Mercado said, "Naw, no, no. I got the Disco Dance Dimensions for the intermission show. I don't see no need for you to be out there. That's not what the people want." Feeling hurt and upset, Eddie explained his frustration to Tito, "I'm not asking for money. I just want to go out and do my thing with you." Tito assured him, "Don't worry about it, baby. I'm gonna bring you in as the Tito Puente Dancers and I'm going to tell Ralphy he doesn't have to worry about nothing."

Ralph Mercado, RMM

Ralph Mercado, RMM

The night of the concert, the Disco Dance Dimensions put on a crowd-pleasing show. Immediately after, Tito Puente played Para Los Rumberos, and got the crowd into a frenzy. Then, he signaled the dancing duo onto the stage to perform Palladium Days, a very fiery, intense mambo. Sternly, Eddie forewarned Maria, "I want you to dance blood." They danced as if they were on fire. Tito had a big ol' smile. And a pleased Ralph Mercado looked on from the sidelines. The roaring crowd in the Garden gave them a standing ovation, sending out a clear message: they preferred to see Latin dancing accompanying the Latin music. They wanted to let Ralph and everyone know, "Hey, that's what we want."

After that evening, Ralph Mercado started calling Eddie to do shows with him. In the nineties, Ralphy introduced his own captivating dance troupe called the RMM Dancers, who animate his concerts with sensuous salsa dancing, though Eddie's group continues to appear at RMM gigs.

THE FUTURE

During the eighties, when Maria and Eddie came on the scene, only a few pro dance teams were left. Aside from Ernie and Dottie and the Cha Cha Aces, there was little trace of the powerful Palladium era. It seems the Palladium dancers got so caught up dancing for their own enjoyment that they weren't thinking about future generations.

Early on, Eddie developed a vision: to see Latin dancing evolve to the point of a respected, classic art form. Recognizing the need to pass the traditions of the music and the dance on to future generations, Mr. T. took it upon himself to make it happen. People laughed at him, "Eddie, what are you doing? This dance is dead." But he obstinately continued his mission.

Before Eddie Torres came along, no one had laid down concepts of structure and technique. He has taught thousands of Latin dance aficionados. His children's dance program in the Bronx teaches approximately three hundred children throughout the year including Eddie's ten year old daughter Nadia, who is already a seasoned pro.  The unique idea of offering salsa or mambo dancing to children alongside other dance forms such as ballet, jazz, tap, modern or African, guarantees the future of Latin. The program developed by Eddie is now run by Maria.

The unique idea of offering salsa or mambo dancing to children alongside other dance forms such as ballet, jazz, tap, modern or African, guarantees the future of Latin. The program developed by Eddie is now run by Maria.

HE'S GOT STYLE

When Latin dance first came to NY, it was an open position dance. That means that two dancers would dance in front of each other and there was not much contact, what we know today as partner work. But the second generation after the Palladium got into doing a lot of partner work. There seems to be a fascination for inventing turns and being in touch with the partner.

The Palladium dancers lay down the blue prints of the New York hip style of Latin dancing. "In NY, people like to dress slick, talk slick, to be very bebop jazzy. Especially Latinos. Being born and raised in Harlem carries a certain attitude about how you walk through the streets, attitude about the way you say things and how you use your body language. It carries such a signature that if I saw someone from New York dancing in Japan, I'd know it."

Broadway musicals, Ailey's work, African dancing, and flamenco all were sources of inspiration for Eddie. Watching, imitating, and admiring the people that were the tops, Eddie slowly evolved as a pro. His style results from a true amalgamation of all those that came before him. With an uncanny ability to imitate, he incorporated a little jazz, a little ballet, a little tap, a little modern, and came out with his own style. Observing the different dancers of his time with their own signatures, he picked up from every one of their styles: JoJo Smith's jazz movements and expression of style; Freddy Rios's very Cuban typical style; a little of Louie Máquina. In dancing, that is known as eclectic styling.

THE TORRES REPERTOIRE

The late June Laberta, a ballroom dance teacher, was Eddie's greatest influence. She taught every ballroom dance in the book, but her greatest love was mambo. On many occasions, June accompanied Eddie to the Corso where the odd couple danced up a storm. He was in his twenties, she was in her late fifties. Creating kooky intricate little moves that came from jazz and everything that she knew, the lean Laberta would spin like a top.

June's mentoring was decisive in Eddie's teaching career. She said, "Eddie, I can help you learn the language of teaching." She took him to ballrooms on Friday nights warning, "These people are scholars and aficionados of the dance. If you don't break on the two, if you're not consistent with your timing, or if they ask questions about the theory and you don't know, they'll use it against you." Sure enough, after doing his fancy footwork, he'd hear the dreaded question, "Do you break on the two?" At that time, these theoretical points about clave and dancing didn't jive with Eddie. Fortunately for Eddie, he'd been on two all his life--he just didn't know it. And June continued harping, "It's going to enhance you as a dancer, as a teacher and as a choreographer. You'll go a lot further with this knowledge." But Eddie fought it. Fifteen years went by before he really learned.

Thanks to June Laberta, Eddie's steps all have names. This repertoire of steps and turns, with their corresponding names, provides a way of relating to students academically. Eddie's class syllabus documenting three hundred steps strangely parallels the habits of the old scholars of dance at the ballrooms. His laboratory is self-contained--sometimes steps spring up spontaneously in the class. Sometimes, just fooling around with a little break or phrase, a step is born. Nowadays, part of the fun is to invent a step and then find a name for it.

Today, dancing students are surpassing people who have been dancing socially for many years. Mr. T. gets calls all the time, "I'm a great dancer, people stop to watch me." One visit to a class and they get humbled. Natural talent is a plus, but Torres warns, "Amongst Latinos, we believe that we can walk on the dance floor and we just do it because we're Latinos, we're born with this. This is just not true."

"I've danced out of joy, I've danced out of pain. This is the kind of dance where if you want to jump up and say 'Azucar!' like Celia, and you want to move your shoulders and bob your head, this is where you can do it and it's O.K. It's cool. And it's hip. You can be you."

We must thank Tito Puente for showcasing salsa dancing in most of his concerts and for making his little speech about the importance of the dance when he presents our beloved Latin dancers.

Eddie's accomplishments include his many collaborations with the Tito Puente Orchestra, choreographing music videos for artists like Ruben Blades, Orquesta de la Luz, Tito Nieves, José Alberto El Canario, David Byrne, founding a dance company, dancing for the President George Bush, performing.at Carnegie Hall, the Apollo Theater, Madison Square Garden.