Bandleader, composer, clarinetist, percussionist, back up singer, saxophonist, accordionist, entrepreneurwithin the musical gamut, Johnny Pacheco has played the full scale. Known for his flute and güiro playing, he switches from one instrument to another with ease, always maintaining a consistently swinging sound. At fifty-eight, aside from the gray hair, there is little evidence of the ravages of time. This is probably due to his witty, clever, playful attitude towards lifeone of salsa's cast of characters.

In the early fifties, Pacheco embarked on his musical adventure. A passion for Cuban music swayed him towards típico style playing, which refers to the charanga and conjunto instrumentation popular in Cuba. "At that time, I was so in love with the Sonora Matancera that I wanted to form this type of group, and I started doing different arrangements and different voicing on the horns. And I used to love Arsenio [Rodriguez, blind Cuban tres player]. So I said, 'you know, the combination between Sonora and Arsenio using the tres will give me a nice sound.' So that's when the whole thing changed and I started getting my own particular sound. That's when I called it Pacheco y Su Tumbao." Thirty years have lapsed and Johnny's historic group is still swinging.

He was born in Santiago de los Caballeros, Dominican Republic on March 25, 1935. His dad, Rafael Azarías Pacheco, was the top Dominican clarinetist and conducted the Orquesta Santa Cecilia, the number one orchestra in that era. Young Johnny always visited the local radio station Nueve HB in Santiago when the band played and never missed the opportunity to hear them perform. Soon he was sitting in a little chair next to where the clarinets played, proudly passing out the sheet music for his father's band. His father gave him a harmonica on Three Kings Day, and by age seven, young Johnny was playing Compadre Pedro Juan, a merengue first recorded by Don Rafael's band, composed by the band's pianist Luis Alberti.

He was born in Santiago de los Caballeros, Dominican Republic on March 25, 1935. His dad, Rafael Azarías Pacheco, was the top Dominican clarinetist and conducted the Orquesta Santa Cecilia, the number one orchestra in that era. Young Johnny always visited the local radio station Nueve HB in Santiago when the band played and never missed the opportunity to hear them perform. Soon he was sitting in a little chair next to where the clarinets played, proudly passing out the sheet music for his father's band. His father gave him a harmonica on Three Kings Day, and by age seven, young Johnny was playing Compadre Pedro Juan, a merengue first recorded by Don Rafael's band, composed by the band's pianist Luis Alberti.

Hector Casanova, longtime singer with Pacheco y su Tumbao (left)

After they relocated to Santo Domingo, Johnny's mom, Doña Octavia, would listen to the soap operas piped in from Cuba. Then, she'd leave the radio on for the rest of the day. At that time, Radio Progreso and Radio Mambi were broadcasting Arcaño y sus Maravillas, La Orquesta Ideal, El Sexteto Habanero and Arsenio Rodriguez. Through these broadcasts Johnny absorbed the many musical influences that would mark his style.

THE GOOD OL' BRONX

But he didn't study music in the Dominican Republic because in 1946, at age eleven his family moved to New York. He went to public school in "the good ol' Bronx," in a neighborhood that felt like war-torn Korea. "There were five of us, a sister and four brothers and we had to kick ass to survive. There was a little street gang. Once they saw you weren't chicken, you became part of the thing." But he managed to stay out of trouble because of his involvement with music. In school, he learned to play the clarinet and the saxophone... and he played stick ball.

In high school, following in the footsteps of one of his brothers who was an electrical engineer, Johnny took up electrical technology. While studying at Bronx Vocational, he put together a mambo band. Barry Rogers, a fellow student who was studying to be an auto mechanic, was the trombone player. Rogers soon followed Johnny's example and became a full-time musician, but he continued working on cars as a hobby.

The members of the band included Johnny on saxophone and Eddie Palmierion piano. That same year, Barry bought a hearse, so they rehearsed in the hearse and they rode to the gigs in the hearse. This was around 1954 and the mambo was in vogue.

The members of the band included Johnny on saxophone and Eddie Palmierion piano. That same year, Barry bought a hearse, so they rehearsed in the hearse and they rode to the gigs in the hearse. This was around 1954 and the mambo was in vogue.

The group's biggest hit was their version of Dragnet Mambo, recorded by Machito for Seeco Records in 1954. Their instrumentation consisted of alto sax, trombone, piano, bass and a full rhythm section. They were playing weddings. The band members related like family. But Eddie always arrived late, according to Johnny, so one day, Johnny had to replace him. It was a painful decision.

Later, Johnny continued studies at Brooklyn Tech and excelled in all his courses. All the while, he continued to play music gigs till graduation. But it came as quite a shock when Pacheco started hunting for jobs in the technical field, that all he could muster was a measley $35 a week... before taxes.

One day, Luis Quintero called him and asked, "You still play the accordion? We're going to play in Villa Perez and we'll give you ninety five dollars for the week-end, plus room and board." This was a meaningful amount to Johnny, so without wasting time, he put away his engineering tools, became a musician and never turned back.

Then Johnny started working as a percussionist. His friend Willie Rodriguez was drumming with the Paul Whiteman Orchestra, the number one big band in New York. "He called me because I think I was the only bongo and conga player that could read music. Whenever they had Latin percussion, they used to call me, so I did the Steve Allen Show and the Johnny Carson Show." In return, Pacheco booked the Tonight Show band for all the Perez Prado recordings, hiring the likes of lead trumpet Doc Severinson.

THE PACHECO COWBELL

When Johnny Pacheco started playing percussion, cowbells were not commercially available. This is why New York timbales players took to tracking down horse drawn carts with the copper cowbells hanging from the horses' neck in order to snip them off. "I remember one time, a horse had one hanging from its neck and I tried to cut it. The driver came and knocked the hell out of me. They caught me with the evidence. It was a beautiful bell."

During his stint as percussionist, Pacheco tried building a pair of congas. He did the wood work and hired someone who was working on a project for the Air Force to do the iron work. While visiting him, he found a piece of metal on the floor and Pacheco instinctively picked it up and hit it with a wrench. It let out a ring that echoed in Pacheco's ear. "Jesus Christ, I've gotta make a cowbell," he echoed back. Then Pacheco produced and sold a number of these cowbells. The first prototype bell still makes occasional guest appearances on the Pacheco bandstand.

PACHECO Y SU CHARANGA

In the fifties, Johnny Pacheco and Charlie Palmieri formed a quintet and started performing in the Catskill Mountains and several local clubs. When Fajardo Y Sus Estrellas played at a political function for Senator John Kennedy in New York's Waldorf Astoria in 1958, they also made a detour to the world famous Palladium to entertain the city's nightbirds. Since Pacheco and Palmieri were playing at Jack Silverman International around the corner, they went for a listen. José Fajardo's Cuban show impacted Latin music lovers and paved the way for the charanga craze.

By 1959, the economic and cultural ties with Cuba had been severed, so the moment was ripe for Charlie and Johnny to start a charanga group. "We completely changed the sound of NY Latin music because the charanga is played with flute and violins, two voices in unison and the rhythm section; timbales, güiro and conga. That's the typical Cuban sound." They called it Orquesta Duboney.

After experimenting with the charanga sound and recording an album for United Artists, Johnny and Charlie realized that their musical tastes were different. "Charlie was one of the greatest pianists ever in Latin music. He was a great arranger, but he used to write very busy, and I like simple things. I used to do most of the arranging and writing. He was not a composer. When we finished recording, he had his idea of a charanga and I had my own. And that's when we split." Because the band members loved each other so much, they opted to flip a coin to decide who would remain with whom. "When we finished, Charlie got a bottle of rum and we celebrated."

Pacheco organized his own band and started shopping it around town. Nobody wanted to record the new group, so he went into a studio and recorded a demo. He laid down two tunes: El Güiro de Macorina and Oyeme Mulata, then paid a visit to Rafael Font, a DJ who loved charanga, pleading, "Coño, can you play this for me?" Font loved what he heard and predicted a hit.

"I didn't know they flooded the radio station with calls trying to find out where to get the record. It became an instant hit and since Al Santiago had a record store, the people went over on Saturday and said, "I want to buy that thing on the radio, El Güiro de Macorina ." Al said, "Who the hell is Güiro the Macori?" Nobody knew who recorded this thing. It was just a demo." That Sunday, Johnny was playing at a club called the Tritons in the Bronx when Al Santiago walked in. "I don't think the band had reached its eighth bar, when I said,

"You want to record, kid? I'll give you a contract," remembers Al Santiago, owner of Alegre Records. (See photo at left)

"You want to record, kid? I'll give you a contract," remembers Al Santiago, owner of Alegre Records. (See photo at left)

THE ALEGRE YEARS - Al Santiago

Pacheco signed with Alegre Records and in 1960, Johnny Pacheco y su Charanga Vol. 1 - Alegre's first album release - exploded. It sold 100,000 albums in six months and became the biggest selling album in Latin music history up to that point. "If I had known it would be so hot, I would have put the record out myself, but I had no idea," regrets Pacheco.

While working at the Tritons, Johnny gave birth to a dance called the pachanga. As he slid from side to side, trying to tap dance like Honi Coles, the audience imitated him and when the musicians wiped their brows with a handkerchief, the crowd thought it was part of the new dance. When the pachanga with the hankie and the hop first became popular in 1961, people thought the word pachanga was a result of combining the words Pacheco and charanga. Although the origin of the word pachanga is not known, the term was actually chosen in a meeting with Pacheco, Tito Rodriguez, Al Santiago, Charlie Palmieri, Federico Pagani and a representative of music publisher Peer International.

Under Al Santiago's creative leadership, Alegre Records grew into a powerful catalyst, experimenting with instrumentation and new musical ideas. Among the musicians Pacheco brought to Al's attention were Barry Rogers, singer Federico "Chivirico" Dávila and timbalero Orlando Marín.

In 1961, Al Santiago created the Alegre All-Stars, echoing the famous Cuban Jam Sessions on the Panart label. Johnny Pacheco recruited his buddy, trombonist Barry Rogers to play with the Alegre All-Stars, a band which featured a unique instrumentation of flute, tenor sax and trombone.

Al Santiago had a gold mine in his hands, but in 1963 his personal problems began affecting his business, and he ran into financial difficulties. Although Pacheco accounted for about 50% of Alegre's income, Al could no longer pay his commitments. Johnny recorded five albums with Alegre. When his contract expired, he left Alegre Records.

Celia Cruz, Johnny Pacheco &

Celia Cruz, Johnny Pacheco &

Louie Ramirez at Fania Studios,

photo ©Mary Kent 1993. All rights reserved.

FANIA COMES TO LIFE

Towards the end of 1963, Johnny met Jerry Masucci at a Taft Hotel party. They immediately hit it off and Jerry, who was a lawyer, soon handled Johnny's divorce. One day, when they were sitting at a little club, Johnny turned to Jerry and said, "You know, I'm gonna start my own record company." Jerry asked if he needed legal advice. "Yeah," said Johnny, "I'm gonna need a lawyer to get the papers together and I'm gonna need some money, 'cause I don't have any." With Jerry's flair for business and Johnny's musical genius, it was a marriage made in Manhattan. They borrowed $2500 and went into a studio to record.

The first album released on the Fania record label was Cañonazo. At that time, Pacheco switched from charanga band to conjunto, incorporating horns. He was forced to change because all decent violin players wanted to play classical. First he started with two trumpets. Then he started doing different arrangements and different voicing on the horns. He finally honed his own style, a Cuban típico sound using the tres guitar, but a little heavier.

Soon Fania started gathering momentum. The young record company had signed a few musicians and wanted to showcase everybody on their roster. A concert at the Red Garter in Greenwich Village, NYC, in 1968 gave birth to the group-the Fania All Stars. The idea surfaced in Acapulco while Jerry Masucci and DJ Symphony Sid were fishing. Jerry and Sid called their buddy Jack Hooke, who was running concerts at the Red Garter, "Why don't we have a Fania All Star night?"

Alhough only some artists were signed under the Fania record label, the Red Garter concert associated a bevy of names with a budding record company-Fania. The artists who performed that night were Ray Barretto, Joe Bataan, Willie Colón, Larry Harlow, Monguito, Johnny Pacheco, Bobby Quesada, Louie Ramirez, Ralph Robles, Monguito Santamaria, Bobby Valentín, with special guest stars Tito Puente, Eddie Palmieri, Ricardo Ray, Jimmy Sabater, Lalo, Hector Lavoe, Ray Maldonado, Ralph Marzán, Ismael Miranda, Pete "El Conde" Rodriguez, Bobby Rodriguez, José Rodriguez, Barry Rogers, Adalberto Santiago and Orestes Vilató. A two volume set Live at the Red Garter was recorded.

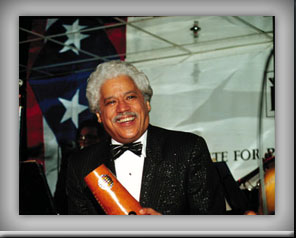

But it wasn't till a steamy summer night, August 26, 1971, in New York City's Cheetah, that the Fania All Stars exploded on the salsa scene. This landmark Cheetah concert consolidated some top Latin bandleaders and musicians as the Fania All Stars under Johnny Pacheco's leadership and for the next 17 years, the All Star group toured the world. These bad boys of salsa chronicled an era and projected Afro-Caribbean music to new heights. The Fania All Stars still get together on special occasions, when they have the time. In February 1993, Johnny Pacheco led the Fania All Stars for a reunion in Caracas, Venezuela in the company of Larry Harlow, Nicky Marrero, Ismael Quintana and Pete "El Conde" Rodriguez. (See Pete in photo)

But it wasn't till a steamy summer night, August 26, 1971, in New York City's Cheetah, that the Fania All Stars exploded on the salsa scene. This landmark Cheetah concert consolidated some top Latin bandleaders and musicians as the Fania All Stars under Johnny Pacheco's leadership and for the next 17 years, the All Star group toured the world. These bad boys of salsa chronicled an era and projected Afro-Caribbean music to new heights. The Fania All Stars still get together on special occasions, when they have the time. In February 1993, Johnny Pacheco led the Fania All Stars for a reunion in Caracas, Venezuela in the company of Larry Harlow, Nicky Marrero, Ismael Quintana and Pete "El Conde" Rodriguez. (See Pete in photo)

Pacheco y Su Tumbao and the Fania All Stars have contributed equally to the legend of Johnny Pacheco. Perhaps, Pacheco's most prestigious role was as organizer and sole bandleader of the Fania All Stars. But on this anniversary commemorating the birth of Pacheco y Su Tumbao, Johnny acknowledges his Tumbao helped him understand the secret to his success: he found a formula. His musical style coupled with his arranging and composing produced a winning combination. "Once you have a formula, you don't change it. The simpler you write, the better it is. This is why Pacheco y Su Tumbao has been around for so many years. Now it's called Pacheco y Su Tumbao Añejo. Añejo means aged, like a good bottle of wine."